MAS's Vision for Stablecoins: A Comprehensive Analysis of the SCS Framework

Singapore's MAS introduced its stablecoin regulatory framework in August 2023. This article examines the framework, examining key insights from a tech-informed perspective.

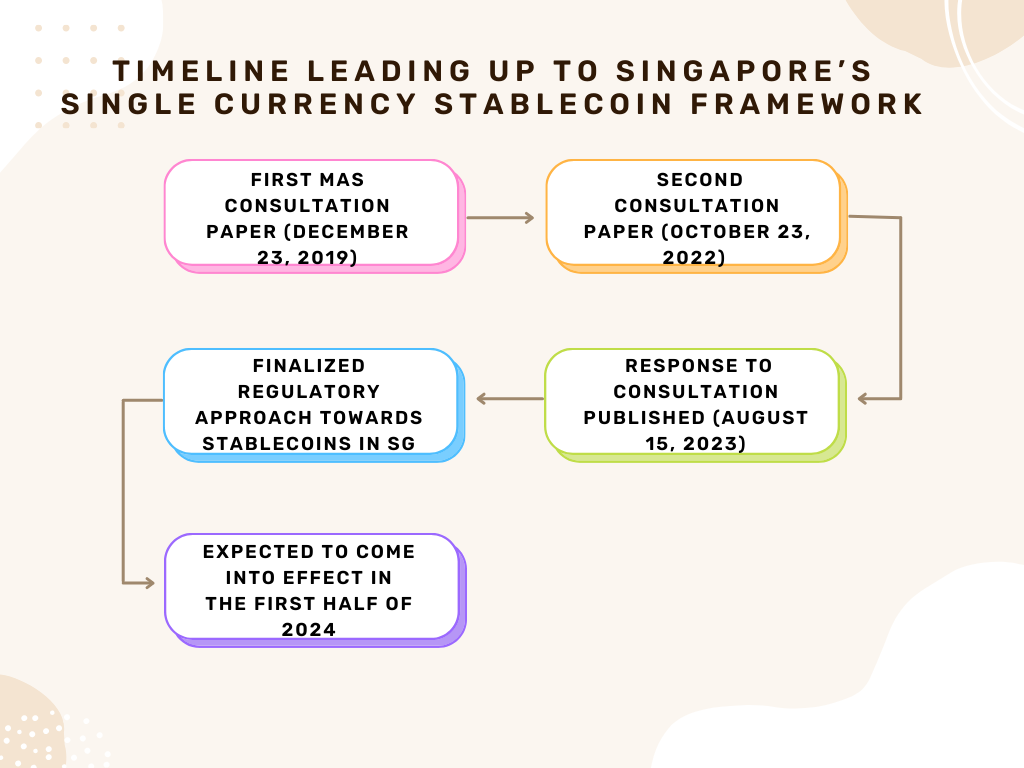

Singapore commenced its exploration of regulatory measures within the stablecoin domain as early as 2019. Following years of meticulous examination and multiple rounds of consultations, in August 2023, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) published a response to its latest consultation, unveiling a comprehensive regulatory framework (“the framework”) for stablecoins, closely aligning with the Financial Stability Board's (FSB) July final report on High-level Recommendations for the Regulation, Supervision, and Oversight of Global Stablecoin Arrangements. This move is expected to bring much-needed clarity to key stakeholders operating within this sector in the city-state.

The framework seeks to ensure a high degree of value stability for MAS-regulated single currency stablecoins (“MAS-regulated SCS”) pegged to either the Singapore Dollar or one of the G10 currencies. These specific currencies are selected based on their availability and status as high-quality liquid assets, making them stand out as robust reserve assets. Stablecoins pegged to a single currency outside this set will be classified as digital payment tokens (DPTs) in relation to the specified fiat currencies and will be subject to regulation under the Payment Services Act 2019 (PSA).

The framework is only applicable to MAS-regulated SCS ‘issued in Singapore’. However, SCS that are issued overseas will not face an outright ban; instead, they will remain subject to the DPT regime under the PSA. MAS has emphasized its commitment to monitor categories of stablecoins that are currently not covered under the framework.

Further, any necessary stablecoin issuance service performed by an issuer, including custody and management of reserve assets, will be considered an ‘additional payment service’ and subsequently be regulated under the PSA. There are also specific instructions within the framework for SCS intermediaries to follow. Where non-issuance activities such as dealing in or exchange of MAS-regulated SCS are concerned, the service provider will be regulated under the PSA, owing to their comparable risk profile with DPT-related services.

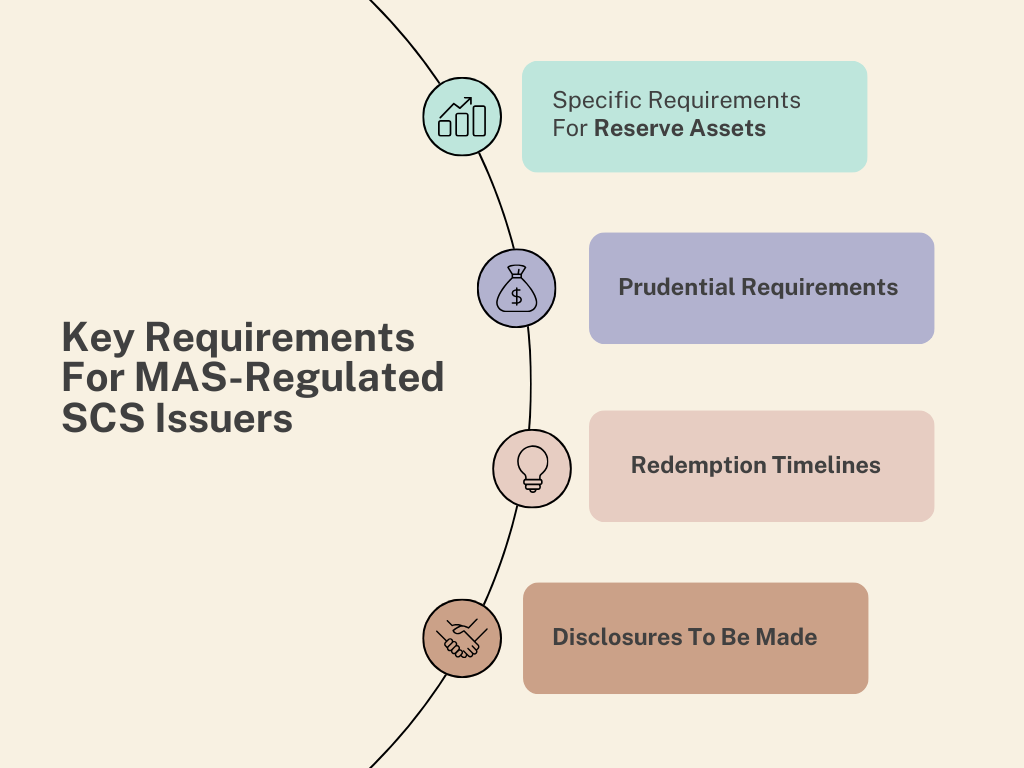

Key requirements for issuers of MAS-regulated SCS:

Reserve assets:

Maintaining a portfolio of reserve assets with low risk;

Such assets to be kept segregated from issuer’s own assets and custody to be held in financial institutions licensed to provide custodial services in Singapore;

Custody of assets with overseas-based custodians may be allowed on two conditions - (a) custodians must have a minimum A- credit rating and (b) custodians must have a branch in Singapore regulated by MAS to provide custodial services;

Reserve assets to be independently attested to every month and published on the issuer’s website.

Prudential requirements:

Minimum base capital (Higher of S$1 million or 50% of annual operating expenses);

Must hold liquid assets at all times, being an assessed amount needed for recovery or an orderly wind-down. Such amount determination should be subject to independent audits on at least an annual basis, to mitigate the risk of insolvency.

Additionally, an issuer will not be allowed to undertake ‘other activities’ beyond their primary activity that introduces additional risks (necessary activities which fall as part of the business will not be considered part of ‘other activities’).

Redemption request: Par value to be returned to holders within 5 days of redemption request (when redeemed directly with the issuer).

Disclosures: Must be made through white papers published on the issuer’s website. These disclosures should encompass critical aspects such as the value stabilization mechanism, holder rights, and the outcomes of reserve asset audits, among other pertinent details.

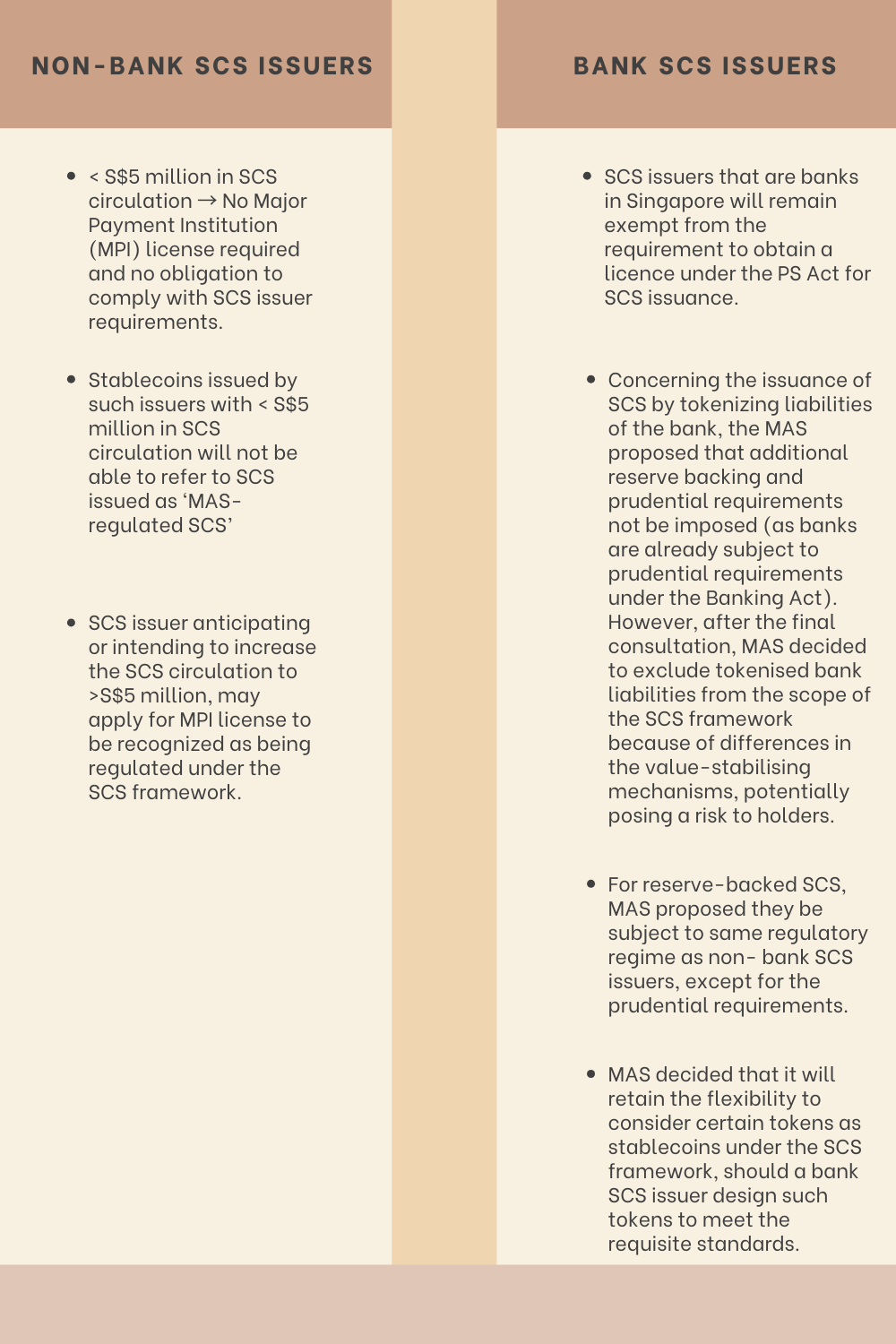

The framework also notably adopted a differentiated treatment for bank vs non-bank SCS issuers.

Key takeaways:

Positively, the framework enforces stringent consequences for the misrepresentation of MAS-regulated SCS by imposing financial penalties and imprisonment in some cases, underscoring the importance of compliance. This accentuates the regulators' acknowledgement of the potential role that properly regulated stablecoins can play in Singapore's financial landscape, as trusted mediums of exchange and catalysts for innovation through the exchange of digital assets.

The MAS has generally adopted a tech-neutral approach to regulating crypto but it is also one of the handful of regulators that has incorporated a tech-informed stance to make sure that existing legislation recognizes distinctive factors about blockchain technology and addresses them. For instance, although the proposed regime is limited to MAS-regulated SCS issued in Singapore, the MAS does acknowledge the fact that not all stablecoins belong to this category and a stablecoin can be pegged against multiple currencies or even other assets. The regulator has narrowed its focus to oversee a specific category of stablecoins while concurrently implementing measures to ensure that stablecoins which fall outside the purview of being recognized as a MAS-regulated SCS operate within regulatory boundaries as well, by imposing the DPT regime upon them and thereby protecting retail customers from the risks associated with non-MAS-regulated stablecoins. The regulator has stated that it is dedicated to vigilant monitoring of these remaining stablecoin categories, carefully assessing whether and when they should be incorporated into the SCS regime.

However, there are aspects that the MAS may need to reassess from a tech-informed lens and consider how they could be more effectively addressed within the SCS framework. The framework’s exclusive applicability to Singapore-based SCS issuers might present challenges not only for international issuers but also for stablecoins that do not have a legally identifiable issuer ( Eg: fully on-chain algorithmic stablecoins such as the Liquidity USD (LUSD), etc.). Since such stablecoins are currently subject to the DPT regulatory regime which does not impose conditions on issuers per se but on DPT service providers, if and when these categories of stablecoins are included in the framework for MAS-regulated SCS, the criteria laid out for issuers should be appropriately adjusted to accommodate such decentralized stablecoins that consist of only a smart contract at the core of its issuing activity and therefore would not be able to comply with all the requirements imposed on issuers. For this category of stablecoins, meeting the framework's requirements may be challenging, prompting regulators to partake in a more comprehensive evaluation of the framework’s suitability in setups where operational dynamics significantly differ from traditional centralized counterparts.

Further, the framework's limitation of "necessary" services that are ancillary to MAS-regulated SCS issuance, such as custody and reserve management, raises questions about the practicality of excluding activities like lending or staking. While it is understandable that the MAS is trying to ringfence risk exposure to SCS by imposing these restrictions, the regulator must also acknowledge that activities such as lending and staking form an integral part of the broader blockchain ecosystem that issuers are generally interested in performing alongside the activity of issuance. While the proposal does allow related entities, such as sister entities that do not have a stake in the SCS issuer to perform these functions, this approach may increase overhead costs in performing activities on behalf of the issuer - in terms of setting up where such related entities are not already established. Moreover, the establishment of a sister entity would not necessarily mitigate the risks arising from lending and staking activities, which have not been actively addressed in the framework. Therefore, these activities will remain to be regulated as part of the DPT-regime where the MAS has only gone as far as to restricting staking and lending services to be extended to retail customers, without venturing further into how to allow retail participation through appropriate regulatory protections. This necessitates a reasonable review of the future iterations of the framework, which might see the merit in allowing issuers to perform extended activities with the implementation of proper safeguards.

Finally, as a matter of suggestion, the MAS has the opportunity to refine its regulatory requirements by exploring avenues that encourage collaboration with law enforcement agencies to establish best practices for handling suspicious transactions. This approach advocates for a cooperative framework where stablecoin issuers voluntarily engage with law enforcement. For instance, within smart contracts, issuers might consider incorporating functionalities that empower them to proactively freeze or block transactions associated with illicit activities. A relevant case in point is Tether (USDT), which recently took a proactive step while assisting the US Department of Justicie’s (DOJ) investigation by freezing $225 million worth of USDT in wallets associated with an international human trafficking syndicate, demonstrating a voluntary commitment to ethical practices.

Global stance on stablecoin regulation

One of the primary use cases driving the adoption of stablecoins revolves around addressing the complexities and costs associated with cross-border trade in diverse currencies. As stablecoins aspire to provide a cost-effective, expeditious, and efficient solution to bridge this divide, the need for harmonization among the laws of different jurisdictions emerges as a critical consideration. Notably, the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdom have emerged as regions that have published some articulated plans in a proactive effort to regulate stablecoins this year.

The EU’s Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) legislation does not use the term ‘stablecoin’ explicitly. However, it recognizes assets of three types, i.e., general crypto assets, asset-reference tokens (ARTs) and e-money tokens (EMTs). Among these categories of tokens, an ART purports to maintain a stable value by referencing another value or right or a combination thereof, including one or more official currencies. In the broader sense of how stablecoins are generally understood to function, stablecoins may be allowed to be issued under the MiCA regime as long as they comply with the requirements laid out for the issuance of ARTs.

Japan has also taken an early adoption approach in the field of stablecoin regulation. With a dedicated bill passed in June 2022, the country has amended its Payment Services Act to formally recognize stablecoins backed by legal tender as digital money, meaning that the holder is guaranteed the right to redeem the stablecoin at face value. The new law came into effect in June of this year.

Most recently though, His Majesty's Treasury (HMT) in the UK published its response to the future of cryptoassets while simultaneously unveiling plans for regulating fiat-backed stablecoins. The HMT's action, aiming for secondary legislation by early 2024, acknowledges the potential of stablecoins to revolutionize retail payments, enhance consumer choice, and streamline operational efficiencies.

These encouraging developments signal the potential for widespread adoption of stablecoins, with regulators and agencies acknowledging their true utility, much like our evaluation of the Singapore framework. However, these regulations may not fully encompass every technological nuance at the moment. These initial steps, commendable as they are, mark just the beginning of a collective effort to comprehensively equip the market. The potential for widespread adoption, efficiency gains in cross-border trade, and enhanced financial inclusivity are tangible objectives, easily achievable by prioritizing a tech-informed approach that accommodates the diverse spectrum of stablecoin innovations.